5 Anchor Principles

Context

Recent reviews of child protection and children’s social care have identified the complexity of the systems social workers and practitioners who every day assess need and risk and design interventions and plans for children, young people and their families. It is a highly pressurised environment with a lot of variables to consider at any given time.

One of the key tools for practitioners has been the use of holistic assessments to identify a need or range of needs of a family and any related risks. In Wirral we underpin our assessments – and the way we work – with a systemic practice model which prioritises the building and understanding of relationships in order to build a picture of the context in which a family may be living, and providing an insight into their lived experiences.

As set out in Working Together to Safeguard Children (2023), the purpose of assessment includes gathering important information about the child and family, from the family and from agencies who hold information about them, and analysing that information to determine a level of need or harm, and then providing the required level and types of support the address the needs and risks and help put the family on a stable footing where all members are safe and can flourish.

One of the key challenges for practitioners undertaking assessments is to understand what a good assessment looks like and to develop good skills of analysis and critical thinking to be able to translate the wealth of information from a number of sources into a coherent and effective plan. The 5 anchor principles provides a framework for doing this.

What are the 5 Anchor Principles?

Research by Brown, Moore and Turney – the authors of the 5 anchor principles identified features of a good analytical assessment (i.e. one which will lead to an appropriate and effective plan).

Using the 5 anchor principles assessment ensures that analysis and critical thinking is an explicit thread running through an assessment process. They can be used at any

stage in an assessment or as a framework for discussion.

The term ‘anchor’ is used because they underpin good assessment practice and help practitioners to become ’anchored’ into what they need to know to analyse assessment practice with children and families.

The authors suggested a good assessment should:

- show an understanding of family history and context

- sets out why the assessment is being done

- provide a good picture of the lived experience of the child and all family members

- be specific about the needs of the individual child

- be logical and show how the conclusions and recommendations have been reached

- make explicit the underpinning knowledge (e.g. child development theory), and evidence (observations and research) which have informed your assessment

- clearly set out your concerns and the reasons for the concerns

- include the views of the child and family members

- be succinct and concise and be jargon free

- contain your hypothesis

- includes the reasoning for your analysis findings (including what you don’t know)

- clearly states what will happen as a result of the assessment

- sets out the plan that should follow

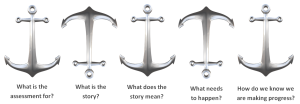

A Five Question Framework for Analytical Thinking

The features of a good assessment, summarised above have been used to formulate five questions to provide a ‘framework for thinking’. The questions follow the process of assessment and provides a useful basis for producing sound analytical assessments, and for testing whether an assessment is good or not. The five questions are:

- What is the assessment for?

- What is the story?

- What does the story mean?

- What needs to happen?

- How do we know we are making progress?

i What is the assessment for?

Research highlights how important it is for social workers and practitioners to be clear about their reason for involvement with a family, and to be able to work purposefully and

collaboratively with families to help them make changes. This question helps the practitioner to consider what they are assessing and what they are involved in the family’s life for.

Being clear about the purpose of the assessment from the beginning will give an

immediate structure and basis for analysis.

This question enables practitioners to demonstrate reflection from the beginning.

Some questions for practitioners to consider are:

- What are you worried about?

- What might the family/child be worried about?

- What skills and support do you need to complete the assessment (e.g. interpreters)?

- Would a chronology of family history and a genogram be useful?

- How will you explain the assessment to the family?

ii What is the story?

These are the relevant facts, circumstances and events. This question supports a practitioner to consider the journey of a family and the lived experience of the child.

Some questions for practitioners to consider are:

- Can you tell the story from the viewpoint of the child?

- How have you used the story to make sense of the child’s life?

- How does the story make you feel?

- Do different practitioners hold different stories?

- Have you thought about how your own past experiences have influenced the story – think about your own social GGRRAAACCEEESSS?

- What is the most important issue for you, and why?

iii What does the story mean?

At this stage, the practitioner will begin to analyse the story using their own practise wisdom, research and expertise about the family. This is the principle whereby you will ‘show your workings out’.

Some questions for practitioners to consider are:

- What hypotheses have been developed and what are the alternatives?

- What is the impact of the story upon the child?

- Imagine the child is in this room – what would they say about the meaning being made of their life?

- How might social GGRRAAACCEEESSS influence how the story is understood by family members?

- What have you not been able to find out?

- Is there any disputed information?

iv What needs to happen?

Plans are now starting to emerge and solutions are now being suggested. Practitioners should focus on the needs of the child or family, rather than describing need, i.e. ‘the child needs to be in a safe environment where there is no domestic abuse’, rather than ‘referral to domestic abuse service’.

Some questions for practitioners to consider are:

- What would have to happen for this child for you to stop being involved with the child and family?

- What do you think will be the best outcome and why? What does the child and family want to happen next?

- How will this be helpful to the child’s current situation?

- Is the family able to make the necessary changes?

- What support does the child/family need and how is that going to be provided?

v How do we know we are making progress?

Practitioners are encouraged to consider what things need to look like in order to be encouraged that the child is safe and their needs are being met. We should consider what ‘good’ looks like in the life of a child and how we will know the family have achieved that.

Some questions for practitioners to consider are:

- What did you hope would have happened by now?

- What would the child/family say? What are there immediate priorities?

- Do you have a plan to challenge family or other professionals involved, should there be no change for the child? Are there service gaps hindering progress?

- What is working well and what is not working well, and what is the plan to change that?

- What changes do you want to see?

Features of a Good Analytical Assessment

From Brown et al, 2012, the features of a good analytical assessment are presented in the one side document below:

Systemic Practice

Systemic Practice is well researched and has been shown in the field of social work to achieve better outcomes for families, decrease children coming into care and increase positive family engagement. It is a way of working which focuses on people’s relationships as a way of making sense of their experiences.

The systemic relationship based practice approach is fully compatible with the 5 anchor principles as they are both centred in understanding the lived experience of the child and family, and share many concepts such as the use of hypothesis, families stories, impact of social GGRRAAACCEEESSS, and understanding that there are things we might not know during the assessment process. Practitioners in Wirral who have been trained in the systemic approach will be able to easily adopt the 5 anchor principles into their assessment practice.

Supervision

The self-check questions included above can also be used in supervision by practice supervisors/ team managers to help practitioners reflect upon and think through their assessment and working with the child and family to ensure the assessment is analytical and can lead to an effective plan.

Research in Practice have published more detailed guidance for practice supervisors about using the 5 anchor principles in supervision, which is included below.

Resources

7 Minute Briefing:

Analysis and Critical Thinking in Assessment (RIP Presentation)